Inside the groundbreaking 1997 all-women Quake tournament

For Quake's 25th anniversary, we look back at a first-of-its-kind moment in FPS history.

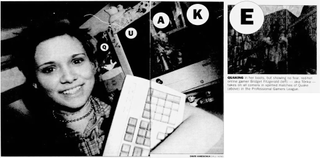

On her first trip away from home, in a Burbank, California mall filled with CRT monitors and Quake fans, Lorie Kmiec Harper's mouse broke. It was 1997, and Harper, a 23-year-old assistant warehouse manager from Ontario, was playing as a finalist in the first-ever All Female Quake Tournament under the handle Temperance.

"I don't know how attached you are to your mouse, but for gaming purposes, it was really bad timing," Harper says on a FaceTime call. She had spent the month before the tournament training with people all over the world, sometimes in the middle of the night. It was the first time she'd gotten a passport, and she was excited just to have made it to LA with her plus-one—her then-boyfriend, a computer engineer who had built her first gaming rig.

"I got kicked out first, you know that, right?" says Harper. "I was number one in Canada, or I was that year. But I was eighth in the world."

Carmack didn't think there were enough women for a tournament. So they made a bet.

The other finalists came from all over North America: Bridget "t0nka" Fitzgerald blew off her freshman orientation at Juilliard to play at the finals ("My teacher was like, you are leaving to do what?" she said). Kornelia Takacs had made a name for herself at the GDC Ten Tournament earlier that year. Stevie "Killcreek" Case was a competitive player infamous for beating Quake designer John Romero in a highly publicized deathmatch. Rounding out the final eight were Aileen "Shadyr" Carlstrom, Mars, LaEl, and Queen Beeatch.

Case was favored to win, according to a New York Times article from 1997, but Takacs triumphed. "No two matches are ever the same. [Quake] reminds me of chess in a way," writes Takacs in an email. "One of my role models is Judit Polgár, one of the best chess players in the world."

The All Female Quake Tournament was a pioneering event in esports, a fact established by its origin. While women in esports still face hostility and skepticism today, the existence of a women's tournament wouldn't be surprising. In 1997, however, the AFT only happened because of a bet.

The bet

The tournament was created by Anna "NabeO," who still prefers anonymity to keep the focus on the competitive players. In the lead-up to the tournament, she did her best to stay in the background because she'd started getting hate mail. Anna was fed up with the perception that there weren't many women who played videogames, much less Quake. "It became so annoying that I thought I should get a bunch of girls to form a clan and play together at a competitive level," she says. "I guess that's where the idea of a female tournament started."

PC Gamer Newsletter

Sign up to get the best content of the week, and great gaming deals, as picked by the editors.

After contacting id Software for its official blessing, she ran into a snag: Nothing was going to happen without cofounder John Carmack's approval, and Carmack didn't think there were enough women for a tournament. So they made a bet. "I think we bet something silly like $100 or something insignificant. It was the bragging rights that were important," she says.

Armed with $1,000 of her own money, a home fax machine, and id's public backing, Anna got to work and ended up with more than 800 registrants. It was the first tournament of its kind for the wildly popular shooter, which was, like esports today, dominated by men. After securing sponsorships from Total Entertainment Network and Burbank's Slam Site, the game was on.

For Harper, the AFT was definitely not the same as what she was used to at home. She played Quake online, on a 14.4 or 28.8kbps dial-up connection. Once in California, she realized that playing on a LAN meant there wasn't any lag. "[When] I'm playing on a server, I have all this lag, and I'm able to do rocket jumps [and get away in time]," she recalls. Fitzgerald agrees—the lack of lag threw off her timing and made it impossible for her to play her best, even after a childhood of attending LAN parties in New York with her brother.

Even then, being eliminated wasn’t a total loss for Harper—the tournament organized trips for them to Disneyland and Universal Studios as a consolation prize. "Everybody was having a good time. I know this sounds terrible, but [girls] didn't take it quite as seriously," she says. "We thought the whole concept of the game was fun."

Eyes on the prize

Not everyone felt the same. Takacs was one of the world's first professional esports players and also participated in QuakeCon, The Frag, the GDC Ten Tournament, and the Cyberathlete Professional League in the late '90s and early 2000s.

"The All-Female Tournament was tough, because I did not have a lot of tournament experience at that point and while at QuakeCon I would be happy to place in the top 16, at a female tournament placing second was not an option for me," says Takacs.

Fitzgerald, the Juilliard student, fell somewhere in the middle. She was serious about her music and mostly saw games as fun.

Takacs, Harper, Fitzgerald, and Anna all have cherished, positive memories of the AFT, but for some, the prizes were a point of contention. Amid the software, autographed Quake swag, and computer parts were also custom wedding garters and cosmetics. Kornelia's was black. Harper's was "like a pale, robin's egg blue" and had the Quake symbol on it. Fitzgerald says the choice of gifts "didn't even register" at the time.

Looking back, Anna, who organized the tournament, doesn't see anything weird about the prize choices. "People like to cherry pick what they want to remember, but there were tons of little gifts that I put together to try to make it fun and intimate… I don't personally think, then or now, that these things are shocking gifts to be given from one girl to another. When I have a girls get-together, I still do this!"

Toxicity, then and now

Online multiplayer was different in the '90s. Quake didn't have a chat feature, much less voice chat, and Fitzgerald often had to find players on IRC. "You had to get an IP address, someone had to host it, you couldn't just fire up the old console and hit roulette or whatever ... I did not like playing with random people, because, you know, men." There also weren't as many people online, which somewhat encouraged self-moderation if you still wanted people to play with you.

"If you became a dick, they were like 'buh-bye' and they would kick you out," says Fitzgerald. She recalls that online shit-talking became gendered when they found out she was a woman. Her original online handle was a variation of "Tank Girl"—the comics and the 1995 film were a huge influence on many girls in the 1990s. "I changed my name to t0nka, because I was like, I don't need [this harassment]," she says.

"There was a lot of hate," Harper says. Men simply didn't want to get beaten by a woman, and sometimes didn't believe she was a woman. "Like right now you can say fine, I'll livestream my game right now with you. We didn't have that technology back then," she says.

Case has spoken previously about the harassment she faced. "People would dig up old pictures of me in high school and new pictures and write these elaborate multi-page teardowns of every aspect of my being," she said in a 2016 interview with the Techies Project. "At one point an ex-boyfriend posted a lengthy insulting, derogatory post on one of the biggest gaming blogs at that time."

Takacs, meanwhile, says she didn't experience negative treatment for being a woman. "Neither for being a left-handed gamer, a Hungarian-born gamer or a female gamer," she says. "Back then I was not out of the closet, but I assume that would have been accepted as well by most gamers."

For Fitzgerald, sexism in the early days of pro gaming was an extension of the "peak misogyny" of the '90s, as she describes it. What she saw and experienced online was what she saw and experienced everywhere else. "I didn't have TV until I was like 13," she says. "I'm the same age as Chelsea Clinton ... and the way they would talk about her on television … I was like 'Mom, what is television?!'"

When I tell Kornelia about the kind of harrassment women in games face today—Gamergate, doxxing, death and rape threats—she's visibly shocked.

The culture has changed, but much has stayed the same or intensified. With social media and far more ways to harangue and attack people, harassment has arguably become more dangerous. In 2016, professional League of Legends player Remilia, who died in 2019, quit the sport due to anxiety and stress stemming in part from sexist and transmisogynist harassment. One of the world's best Overwatch players, Geguri, considered using software to deepen the sound of her voice. The subject of women's-only tournaments are hotly debated as either unnecessary or a painfully slow stepping stone to eventual progress. 90% of esports scholarships still go to men.

Women's game tournaments today don't share much in common with the AFT and Anna's personal effort to bring an unprecedented tournament to life. It was a landmark event at the time, though, and remains a bright spot in women's gaming history and gaming history as a whole.

Alexis Ong is a freelance culture journalist based in Singapore, mostly focused on games, science fiction, weird tech, and internet culture. For PC Gamer Alexis has flexed her skills in internet archeology by profiling the original streamer and taking us back to 1997's groundbreaking all-women Quake tournament. When she can get away with it she spends her days writing about FMV games and point-and-click adventures, somehow ranking every single Sierra adventure and living to tell the tale.

In past lives Alexis has been a music journalist, a West Hollywood gym owner, and a professional TV watcher. You can find her work on other sites including The Verge, The Washington Post, Eurogamer and Tor.

Most Popular