The last fifteen years has seen a surge of interest in decentralised technology. From well-funded blockchain projects like IPFS to the emergence of large scale information networks such as Dat, Scuttlebutt and ActivityPub, this is renewed life in peer-to-peer technologies; a renaissance that enjoys widespread growth, driven by the desire for platform commons and community self-determination. These are goals that are fundamentally at odds with – and a response to – the incumbent platforms of social media, music and movie distribution, and data storage. As we enter the 2020s, centralised power and decentralised communities are on the verge of outright conflict for the control of the digital public space. The resilience of centralised networks and the political organisation of their owners remains significantly underestimated by protocol activists. At the same time, the decentralised networks and the communities they serve have never been more vulnerable. The peer-to-peer community is dangerously unprepared for a crisis-fuelled future that has very suddenly arrived at their door.

“Good luck to all those striving for decentralization, balance and equality in the world. You are fighting the right battle. This battle may well be the most important battle of our generation.”[1]

“‘Torrents are down, worldwide’ said no one, ever. #centralizationisfragile”[2]

How precarious are decentralised networks? Answering this requires an understanding of both the power of their political energy and history of antagonism. Conceptually, peer-to-peer technologies are not new – they are networks of digital topologies, intertwining configurations of software clients, devices, connections and protocols whose ownership is distributed. They work in concert to provide a robust alternative to centralised governance, ideally achieving data resilience without transferring the ownership of this data to a single authority. The internet itself is a decentralised network.

Often – but not always – decentralised networks emerge due to a collective desire to rebalance societal power[3]. One of the antagonisms that brought these tensions to the boiling point was the series of legal battles over digital intellectual property rights. This conflict – a so-called Copyright War – had started “offline” decades earlier[4], but collided with digital infrastructure for the first time in 1999 with the launch of Napster. Its trajectory would last over a decade and the fallout reverberates into the present. To understand the Copyright War is to understand how close copyright reformists came to dismantling an existing centralised data ownership structure, and how they failed to appreciate the resilience of this opponent as it economically and legally exploited their peer-to-peer model.

Early file-sharing software featured simple interfaces and enormous content offerings. They arrived years before popular digital music stores, and as such Napster and its clones shook the music and movie industry into mobilising against them. These networks were tied to their client software, and by targeting their developers with litigation, were easily shut down. Copyright reformists first campaigned on behalf of Napster and similar tools, but as residential bandwidth scarcity and demand for data freedom grew, these activists saw new promise beneath the application – an opportunity embedded in the network layer.

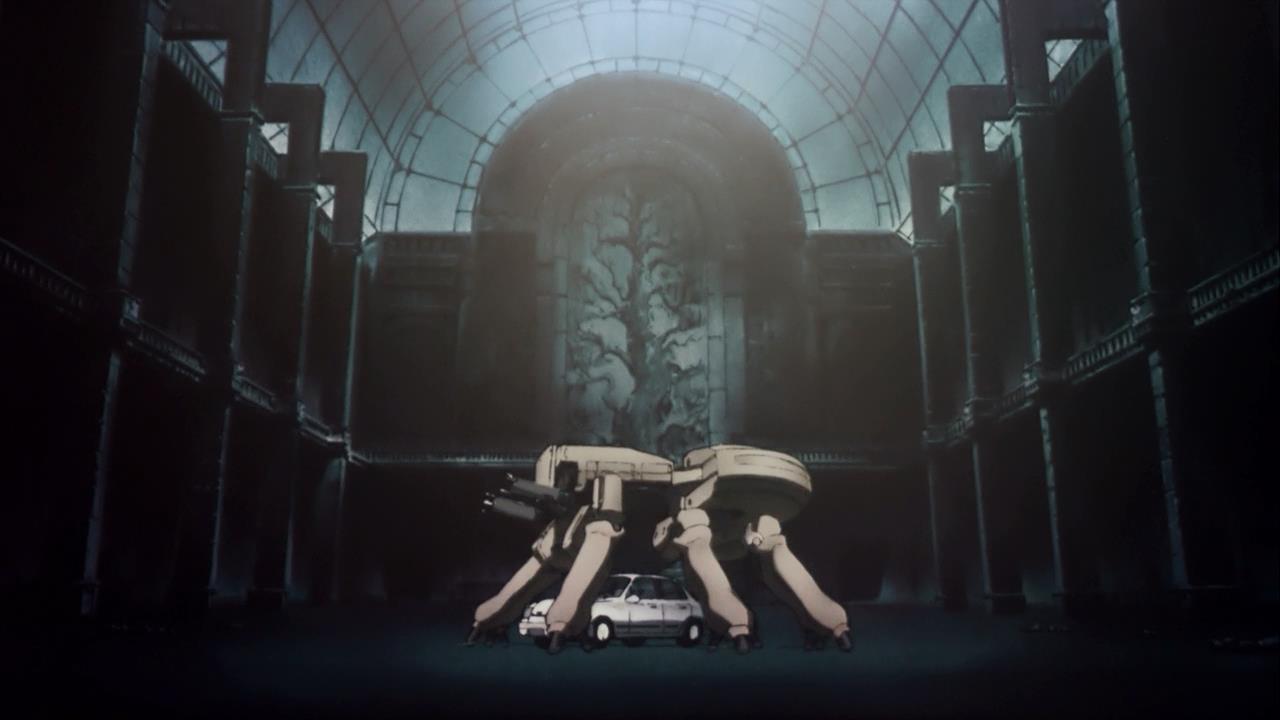

BitTorrent’s launch in 2001 enabled file-sharing on a massive, efficient and resilient scale. By embedding the decentralised ideology beneath the desktop client, and within the protocol on which the client runs, the act of file-sharing became much more resistant to legislative attack. To many of its supporters and combatants, BitTorrent seemed unstoppable. Most of the early 2000s discourse prophesied the devastation of an existing capitalist cultural order, accelerated by significant ideological moments of the era: the establishment of the first collaborative online music library[5], the foundation of the Pirate Bay website, censorship-resistant document distribution, and the formation of the Piratpartiet[6], and its international equivalents[7].

The incumbent powers worked with lawmakers to draft new legislation and went after ‘leechers’ - people downloading content, but who through BitTorrent’s protocol design became unwitting uploaders themselves[8]. Litigators discovered that by conducting surveillance on a BitTorrent tracker, they could bulk collect participating IP addresses and randomly file severe civic lawsuits, utilising harsher laws reserved for distribution. Their targets were often the economically vulnerable, including “children, grandparents, unemployed single mothers, college professors—a random selection from the millions of Americans who have used P2P networks.”[9] It was one piece of a broader scattershot strategy that spared no one; infrastructure[10], physical media[11], broadcast media, adjacent software projects and device manufacturers were all targeted. These tactics could manifest as copyright taxes on CD–Rs or portable media players, or in the form of legal liability, such as unsuccessful proposals for ISPs to bear responsibility for user activity.

The entertainment industry framed the conflict as a fight against movie and music “piracy.” However, this rhetoric obscures the serious implications of the tactics deployed by these giants. Central to the defeat of this particular peer-to-peer movement was that its infrastructure was vulnerable to weaponised design[12], in which the network protocol directly empowers attackers through its design. For BitTorrent, this empowerment came as the protocol exposes every user’s participation in the network. This data was exploited to unmask users, ruin lives and provide justification for new legislation. The collapse of centralised power that was prophesied in the 2000s never materialised. Centralised actors outmaneuvered the reformists, shielding themselves and their own ecosystems from scrutiny. The concentrated media companies of the 2020s now dwarf their 1999 equivalents[13], and the innovations pioneered by decentralised infrastructure were exploited by the winners as they ascended to monopoly.

The most poetic example of peer-to-peer technologies pressed into the service of corporate giants is the story of peer-to-peer software engineer Ludvig Strigeus. Having built the popular μTorrent client and perhaps sensing the changing winds, Strigeus joined former μTorrent CEO Daniel Ek’s new startup. Together, they built a quasi-Napster/BitTorrent hybrid that relied on a vast, unauthorised music catalog drawn from its user base[14]. Today, that architecture is long gone, but the startup – Spotify – boasts 124 million subscribers, taking in USD$7.44 billion in revenue but paying artists just USD$4.37 per 1,000 streams[15].

As we can see from history, blind faith in technically resilient network protocols is naïve and misplaced. The Copyright War drives home hard lessons around politics, corporate appropriation, transparency, collectivism and the urgency of network safety, all illustrated in the decimated lives of key or adjacent reformists[16], collateral user damage, and resulting legislation[17]. In 2013, BitTorrent was responsible for 3.35% of all internet traffic[18]. Today the networks remain but this market share has shrunk. Torrents are down worldwide.

“Only a crisis — actual or perceived — produces real change. When the crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around. That, I believe, is our basic function: to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes politically inevitable.”[19]

“Your objective [as a designer] should always be to eliminate instructions entirely by making everything self-explanatory, or as close to it as possible. When instructions are absolutely necessary, cut them back to a bare minimum.”[20]

As the Copyright War faded into the background, the iPhone paradigm – a constrained, centralised, individualised system marketed as “the individual at one with their device” – became the standard for personal computing. New and boundless design-led opportunities appeared almost overnight, powered by a bottomless injection of venture capital that fostered the accelerated growth of platform capitalism[21]. To quote design and art historians Arden Stern and Sami Siegelbaum:

“Neoliberalism can be distinguished from Fordist capitalism’s mass production of consumer goods by the ways it seeks to marketize previously uncommodified sectors of human life. Indeed, one of the questions [we seek] to explore is how design might enable this process by locating new sources of extraction and accumulation by facilitating the commodification of that which was once thought to be outside the scope of the market.”[22]

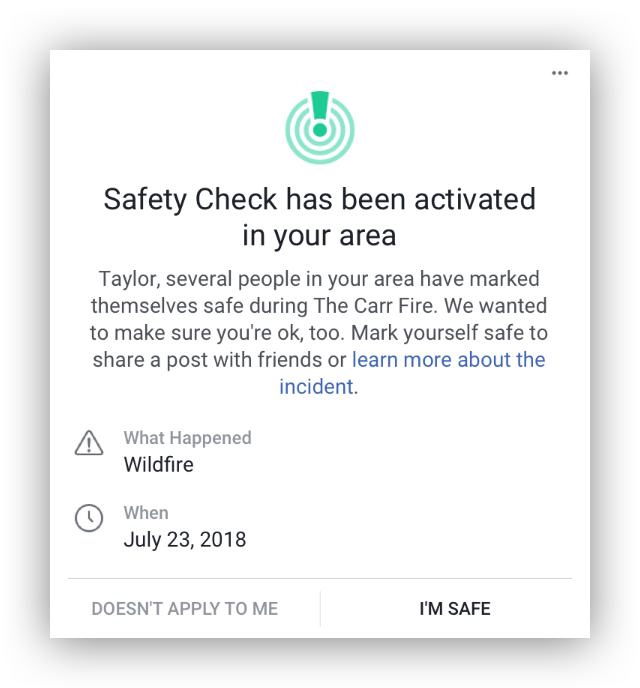

Finding these new sources of extraction became a priority for centralised tech platforms. They had spent the previous decade achieving scale and resilience; now they sought to extract new value and justify their presence in daily life. Framing the mobile device as an extension of self made the emergence of the new ‘digital wellbeing’ market compelling. For example, Safety Check[23] – a Facebook feature introduced after the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami – encourages users in disaster-stricken areas to interact with the platform to mark themselves as safe and be connected to communication services for disaster relief. The Apple Watch – originally launched as a general-purpose wrist computer – underwent a complete rebrand as a digital health and fitness device, and its ability to detect and call emergency services in crisis is actively marketed in emotional video testimonials released by its maker. Amazon Ring and Google Nest encourage consumers to actively contribute to a growing network of community surveillance systems promising safety in exchange for ceding the household’s digital capital to a powerful, unaccountable platform.

These tech-driven efforts to respond to safety and crisis are not new, and indeed much of this work is framed both internally and externally within the cliche of “making the world a better place”[25]. But these efforts also serve a dual function; they are political tools that through design can instantly reconfigure a moment in time. An Apple Watch is marketed to the physically vulnerable senior citizen, but the same interface has been programmed as a digital bystander, bearing witness on behalf of Black Americans during traffic stops[26]. Effective design at scale is obvious and frictionless – lowering cognitive and training barriers to adoption – and contextually voided – enabling context to be re-inserted after the design is shipped.

In her 2007 book, The Shock Doctrine, Naomi Klein lays bare the clandestine policies employed by powerful societies to expand influence and ownership through exploitation of real or manufactured crisis. Klein cites societal-wide disasters - the invasion of Iraq as a pretext for greater US control in the Middle East or, most recently, identifying the privatisation of infrastructure after the 2018 Puerto Rico hurricane as the pretexts for this overreach. The ubiquity of human-centred design[27] offers flexible opportunities to use technologies to extract value and consolidate power. The design of the Apple Watch, Safety Check and particularly COVID–19 Contact Tracing APIs[28] must be understood as whitelabelled crisis response – Shock Doctrine as a Service – employing dominant, market-driven design methodologies to drive mass adoption of products and services that are then easily reconfigured during moments of disaster. Presented as opportunities to protect or save lives, these functionalities are rolled out in homes, communities and cities as software updates or addons – without allowing any negotiation or meaningful consent. When deployed in response to broader crises, their creators benefit from being perceived as philanthropic architects, intervening on humanitarian grounds. In reality, they negotiate from positions of extreme concentrations of wealth, technical expertise and political influence[29]. The philanthropic framing robs dissenters of what remains of their ability to withdraw consent: How can one object to saving lives?

“There is a part of my high-school globo-claustrophobia that has never left me, and in some ways only seems to intensify as time creeps along. What haunts me is not exactly the absence of literal space so much as a deep craving for metaphorical space: release, escape, some kind of open-ended freedom.”[30]

“How the fuck do so many Zoomers not know how to torrent things?”[31]

The neoliberal technology order seemed secure in its dominance. The 2016 US elections and Brexit vote changed all that; ugly, internationally visible clusters of ever-escalating patterns of barbaric behaviour perpetuated and enabled by incumbent power. Cambridge Analytica and its clientele were far from the first[32] to manipulate the social graph[33] in the name of electioneering, but these campaigns and their surrounding turmoil triggered a collapse in end users’ trust of centralised platforms. In the years leading up to the election, centralised platforms had been strained by surveillance, manipulated by money, and littered with repeated failures to address abuse. In response, the peer-to-peer communities that had been quietly designing alternatives for years awoke charged and energised; a new wave of interest in decentralisation was emerging.

Who are these peer-to-peer communities? They are developers, designers and early adopters. Their politics are diverse, yet there are areas of consensus. They rally around the values of self expression, alternative data governance, censorship resistance and interoperability. Their communities organise, debate and signal politics through their respective networks, encoding protest in encryption[34], or framing servers as facillitators of self-expression[35]. Common to all of these individuals and communities is a belief in the protocol as a political device. Simone Riobutti describes this as the ‘Hackerist perspective’, an “attempt to alter technology for political reasons by repurposing technological artifacts without concerning oneself with altering the process that produced said technology.”[36] Here, the unaltered process is the process of protocol design by makers who are ignorant to both lessons of the Copyright War and the emerging threats facing their own societies.

In 2017, the Dat Foundation spoke publicly[37] of their desire to build a decentralised, censorship-resistant Wikipedia mirror but shortly after this announcement, the effort was abandoned. The team involved realised that, although Dat archives are encrypted, network participants are as vulnerable and easy to track as the BitTorrent targets from the Copyright War. In a followup blog post entitled, ‘Do Not Ship It’, the team elaborated: “Reader privacy is one of the hardest (ethical) parts of a peer-to-peer system. Distributing Wikipedia over a peer-to-peer system means that any user can surveil the IP addresses of other users and, depending on how it is distributed, even identify what pages they are requesting. For us, this is an unacceptable first-order effect. The impact of this first-order surveillance problem leads us to even more concerning questions about the second- and third-order impacts of that decision.”[38]

The Dat Foundation’s caution over political use of their protocol is at odds with how the protocol is used. A year before, Dat had already been used to archive and mirror climate research that had been politically censored by the incoming Trump administration[39]. Shortly after Do Not Ship It was published, the personal details of thousands of US Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers were scraped from LinkedIn by a protester and posted to GitHub. When Microsoft’s lawyers intervened and removed the archive, it was mirrored to Dat[40]. In both of these instances, the protocol was used in political protests against a belligerent corporate-captured political office. That the protocol was designed without a strong investment into participant privacy directly led to two incredibly dangerous moments for network participants.

Reviewing the technical documentation of the Dat protocol, researcher and privacy advocate Sarah Jamie Lewis expressed her frustration towards its designers’ claims around privacy[41]. She tweeted: “[...] there is a section that reads: "There is an inherent tradeoff in peer-to-peer systems of source discovery vs. user privacy." I disagree with the statement & the impact resulting design decisions have on privacy. [...] Freenet presented solutions to this problem[42] which provided strong guarantees for reader anonymity and publisher anonymity nearly 2 decades ago.” Decentralisation advocates roleplay as antagonists for change, but they have yet to truly threaten incumbent power. Instead, the de-prioritisation of privacy by design – regardless of its justification – enables its behaviour and offers it new scope for surveillance and control.

This is true for many of the communities that have formed around decentralised protocols. On Secure Scuttlebutt, nothing can be deleted or modified, identities are linked cryptographically to individual devices, and the asynchronous nature of the platform is highly resilient – meaning that data can’t be erased[43]. Even the act of changing your name or following or unfollowing someone creates a permanent record. This beautifully designed decentralised network also happens to be a forensically sound surveillance tool, in which nothing can be retracted and proof of authorship can be traced to specific devices. Secure Scuttlebutt has attracted a vibrant community that leans left-wing libertarian, engaging openly and eagerly in post-capitalist discourse and baying for serious alternatives to neoliberalism. This is a dream for network surveillance. The danger could not be more obvious.

The Fediverse – a network comprised of Mastodon, Pleroma and other adjacent projects[44] – suffers from the same glaring contradiction. Similar to email nodes, servers (known as Instances within this network) are branded around common interests, political beliefs or sexualities. Users are encouraged to join the servers that resonate with them. Like Scuttlebutt, political and sexual expression is warmly encouraged; in just one example, after centralised media moved to close the accounts of sex workers to comply with new US anti-sex trafficking laws, a Mastodon Instance named Switter was created to offer space for these individuals to continue to operate safely. Switter is now one of the largest Instances in the network[45].

This collection of networks offers no end to end encryption. Anyone with administrator access to an Instance can read anything that travels through that Instance’s infrastructure – including direct messages. The level of risk correlates with the number of cross-Instance interactions between users. If users from different Instances communicate, an attacker need only compel one Instance to reveal the direct messages between all of the interacting accounts. The centralised equivalents – Twitter, Tumblr, etc – can cloak their users through governance and resources. In a peer-to-peer network without encryption, there’s no structure, no agreed-upon governance, and absolutely no protection. Compromising or compelling an Instance or its staff means that all of network traffic is laid bare to its assailant.

The Fediverse has also grappled with its own limitations in threat modelling, such as failing to collectively anticipate the establishment of far right and fascist political Instances – deplatformed refugees from dominant social media platforms[46]. Can or should a federated network accept ideologies that are antithetical to its organic politics? Regardless of the answer, it is alarming that the community and its protocol leadership could both be motivated by a distrust of centralised social media, and be blindsided by a situation that was inevitable given the common ground found between ideologies that had been forced from popular platforms one way or another.

From the role cryptocurrencies play in emergent dark web marketplaces, to the well-funded efforts by IPFS to produce a ‘faster, safer, and more open internet,’[47] the decentralised community seeks to antagonise a powerful status quo whilst making tradeoffs that do not acknowledge how societies directly threaten their communities. Combined with this antagonism, the lack of investment in privacy techniques as a priority is catastrophic. Users are asked to administrate, govern and participate politically in networks they don’t fully understand. As these networks are decentralised away from concentrated power, their risk, and political and economic capital are equally decentralised. The antagonistic rhetoric of these systems mean that participants are naïve to these risks. Whether pushing for political revolution, offering sex-work online, or buying drugs with cryptocurrency, these participants are as doomed as the victims of file-sharing lawsuits before them.

“Turn your back on weeds you’ve hoed

Silly sinful seeds you’ve sowed

Add your straw to the camel’s load

Pray like Hell when your world explode

Little wheels spin and spin,

big wheels turn around and around.

Little wheels spin and spin,

big wheels turn around and around”[48]

Despite its polished aesthetics and It Just Works mantra, we can almost see these incumbent powers beginning to buckle. Centralised platforms crave data collection and thirst for trust from the communities they seek to exploit. These platforms sell bloated, overpowered hardware that cannot be repaired, vulnerable to drops in consumer spending or spasms in the supply chain. They anxiously eye legislation to compel encryption backdoors, which will further weaken the trust they need so badly. They wobble beneath network disruptions (such as the worldwide slowdowns in March under COVID-19 load surges[49]) that incapacitate cloud-dependent devices. They sleep with one eye open in countries where authoritarian governments compel them or their employees to operate as an informal arm of enforcement. These current trajectories point to the accelerating erosion of centralised platform power.

This global instability demands platform reform. Peer-to-peer networks theoretically offer a level of resilience, safety and community determination that may no longer be possible with these incumbent powers. The moment demands not another protocol, not another manifesto, not another social network, but a savvy understanding of the political dynamics of protocols and the nakedness of today’s networks. By embracing a reverse Shock Doctrine as a Service, developing clear, historically-grounded narratives, and building sensitivity to the user’s abilities and safety, these new decentralisation reformists can succeed where others have failed. Their solution cannot mimic an existing platform, and they must resist the temptation to trust their personal ephemera to the cloud. The phone books, calendars, notepads, photo albums and secrets that communities upload are exactly the debased thrills that extrajudicial perverts hunger after. These communities, their communications, their social graphs and their movements are ripe for exploitation. The only future is one where this is reality is embraced and fought against with every possible effort.

Designers must discard the tools that crush divergence and nuance, such as design thinking[50], user personas and so-called ethical design practice[51]. There is a rich but incomplete field of emergent work to draw from: New frameworks such as Socio-technical Security[52], and Decentralization off the shelf[53], exist to assist protocol designers understand and model interfaces and threats more completely and realistically. We must draw from groups that resist the Californian Ideology’s definition of identity[54], from the 1970s civil-rights aligned student activists who fought against digitised student records[55], to today’s Decolonise Design movement[56]. Decentralisaiton reformists must cede space for decision-making and expertise to under-represented or assailed communities[57].

We can no longer marvel at the novel interactions afforded by peer-to-peer technologies, nor perform political theatrics within these networks. We need to lay aside our delusions that decentralisation grants us immunity – any ground ceded to the commons will be met with amplified resistance from those who already own these spaces. When this happens, every single arrogant tradeoff, every decision made in ignorance that assumes a stable march towards progress without regression will be called to account. Without cohesive organisation, mobilisation to harden security and privacy and without a sincere commitment from protocol designers to revise their collective assumptions, the push back from incumbent power will leverage each and every socio-technical flaw in each and every network. The fallout and trauma for increasingly digitalised communities will unquestionably dwarf the 2000s Copyright War. If there is no collective worldview reset, the peer-to-peer movement will remain a historical novelty, a technological bauble and thought experiment for detached technologists unable to understand the political gravity of their tools, and whose life work will never withstand the attacks against it.

Cade Diehm

Summer 2020

Edited by Edward Anthony. Thanks to Molly Wilson, Eileen Wagner, Rose Regina Lawrence, Roel Roscam Abbing, Karissa McKelvey, Georgia Bullen, Ruth Catlow, Andrew Thompson and others.

What was TON and why is it over?

Pavel Durov, founder of Telegram

12 May 2020 ↩︎@AndreStaltz

André Staltz, Twitter

21 April 2020 ↩︎Information Civics: Deconstructing the power structures of large-scale social computing networks

Paul Frazee ↩︎Home Taping Is Killing Music: When the Music Industry Waged War on the Cassette Tape in the 1980s, and Punk Bands Fought Back

Ted Mills, Open Culture

5 April 2019 ↩︎Related: What.CD (2007 – 2016)

Wikipedia ↩︎Political pirates: A history of Sweden’s Piratpartiet

Nate Anderson, Ars Technica

26 February 2009 ↩︎Related: Pirate Party International

Political Party ↩︎Bittorent Protocol Specification

Bram Cohen, Bittorrent, Inc.

10 Jan 2008 ↩︎RIAA v. The People: Five Years Later

Electronic Frontier Foundation

30 September 2008 ↩︎RIAA drops lawsuits; ISPs to battle file sharing

Greg Sandoval, CNET

12 November 2009 ↩︎Copyright levies

Service public fédéral Justice, Belgium

20 July 2005 ↩︎On Weaponised Design

↩︎16 February 2018 The Walt Disney Company To Acquire Twenty-First Century Fox For $52.4 Billion In Stock

The Walt Disney Company

14 December 2017 ↩︎ Spotify Teardown: Inside the Black Box of Streaming Music

Spotify Teardown: Inside the Black Box of Streaming Music

25 January 2019 ↩︎Quarterly Results (2018 – 2020)

Spotify AB ↩︎Aaron Swartz (1986 – 2013)

Wikipedia ↩︎

↩︎31 May 2006 Bittorrent global usage

Palo Alto Networks ↩︎ Capitalism and Freedom

Capitalism and Freedom

1 January 1962 ↩︎ Don't Make Me Think (2nd Edition)

Don't Make Me Think (2nd Edition)

28 August, 2005 ↩︎ Platform Capitalism

Platform Capitalism

November 2016 ↩︎Special Issue: Design and Neoliberalism

Arden Stern & Sami Siegelbaum, Design and Culture

26 September 2019 ↩︎

Safety Check

Facebook Crisis Response ↩︎The "Dear Apple" campaign explicitly positions the Apple Watch as an essential lifesaving device. (Use video controls to unmute)

Apple PR ↩︎The inside story of Facebook's biggest setback

Rahul Bhatia, The Guardian

12 May 2016 ↩︎“Hey Siri, I’m getting pulled over” iOS Shortcut for recording traffic stops

/u/RobertAPetersen, Reddit

21 September 2018 ↩︎“Human Centered Design”: a design process in which a designer builds a “deep empathy for the people they are designing for.”

IDEO Design Kit ↩︎“The long tail of contact tracing”

@InstitutefTiPI, GitHub Issues

10 April 2020 ↩︎A flood of coronavirus apps are tracking us. Now it’s time to keep track of them.

Patrick Howell O'Neill, Tate Ryan-Mosley & Bobbie Johnson, MIT Technology Review

7 May 2020 ↩︎@Ex_AnarchoAnon

Twitter

16 May 2020 ↩︎How Obama’s Team Used Big Data to Rally Voters

Sasha Issenberg, MIT Technology Review

19 December 2012 ↩︎Do Online Election Campaigns Win Votes? The 2007 Australian “YouTube” Election

Rachel K. Gibson & Ian McAllister, Political Communication

29 April 2011 ↩︎While executing the Bitcoin network’s first transaction, Satoshi Nakomoto embedded additional text into the block: “The Times 03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks.” This is widely interpreted to be ideologically motivated.

The Bitcoin Wiki ↩︎Seven Theses on the Fediverse and the Becoming of FLOSS

Aymeric Mansoux & Roel Roscam Abbing, Institute of Network Cultures

February 2020 ↩︎Against Hackerism

Simone Riobutti

29 November 2019 ↩︎Decentralising Knowledge

Mathias Buus Madsen, P2P Web Berlin

10 February 2018 ↩︎Do Not Ship It

Joe Hand, Dat Foundation

10 November 2017 ↩︎Ensuring access to critical research data

John Chodacki, University of California Curation Center

02 March 2017 ↩︎A List of ICE Employees Scraped From LinkedIn Was Removed by Medium and GitHub

Brian Feldman, New York Magazine

20 June 2018 ↩︎Tweet thread by Sarah Jamie Lewis

@SarahJamieLewis, Twitter

17 June 2018 ↩︎Freenet: A Distributed Anonymous InformationStorage and Retrieval System

Ian Clarke, Oskar Sandberg, Brandon Wiley & Theodore W. Hong, Lecture Notes in Computer Science

March 2001 ↩︎Secure Scuttlebutt protocol whitepaper

Domonic Tarr, Erick Lavoie, Aljoscha Meyer & Christian Tschudin, ACM

September 2019 ↩︎Fediverse.party

A collection of ActivityPub related applications ↩︎Mastodon Instances by User Count

Fediverse Network metrics

15 May 2020 ↩︎It’s time to get serious about sanctioning global white supremacist groups

Daniel Glaser & Hagar Chemali, The Washington Post

11 May 2020 ↩︎IPFS for example raised over $257 million via the Filecoin ICO

Crunchbase Profile ↩︎

↩︎New Global Internet Outages Map: “Concerning” Rise in ISP Outages

Conor Reynolds, Computer Business Review

23 March 2020 ↩︎Design Thinking is a Rebrand for White Supremacy

Darin Buzon

2 March 2020 ↩︎

↩︎ Design Ethics? No Thanks!

Design Ethics? No Thanks!

19 March 2020 Entanglements and Exploits: Sociotechnical Security as an Analytic Framework

Matt Goerzen, Elizabeth Anne Watkins & Gabrielle Lim, USENIX FOCI '19

13 August 2019 ↩︎Decentralisation off the shelf

Eileen Wagner & Karissa McKelvey, Superbloom

2020 ↩︎The Californian Ideology

Richard Barbrook & Andy Cameron, Mute

1 September 1995 ↩︎“Do Not Fold, Spindle or Mutilate”: A Cultural History of the Punch Card

Steven Lubar, Journal of American Culture

Winter 1992 ↩︎Decolonising the Digital: Technology as Cultural Practice

Josh Harle, Angie Abdilla & Andrew Newman,, Tactical Space Lab

15 October 2018 ↩︎ Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code

Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code

17 June 2019 ↩︎

The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism

The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism